Many families throughout the SADC region are dependent on income received via cross-border remittance. Their impact cannot be understated. Cross-border remittances provide these people access to essential services and contribute to micro-economies in many SADC communities thereby fostering regional socio-economic development. In 2022 formal outbound remittances, via authorised dealers or authorised dealers with limited authority, from South Africa totalled approximately 991 million United States Dollars. The value of informal remittances is estimated to be about equal to this amount.

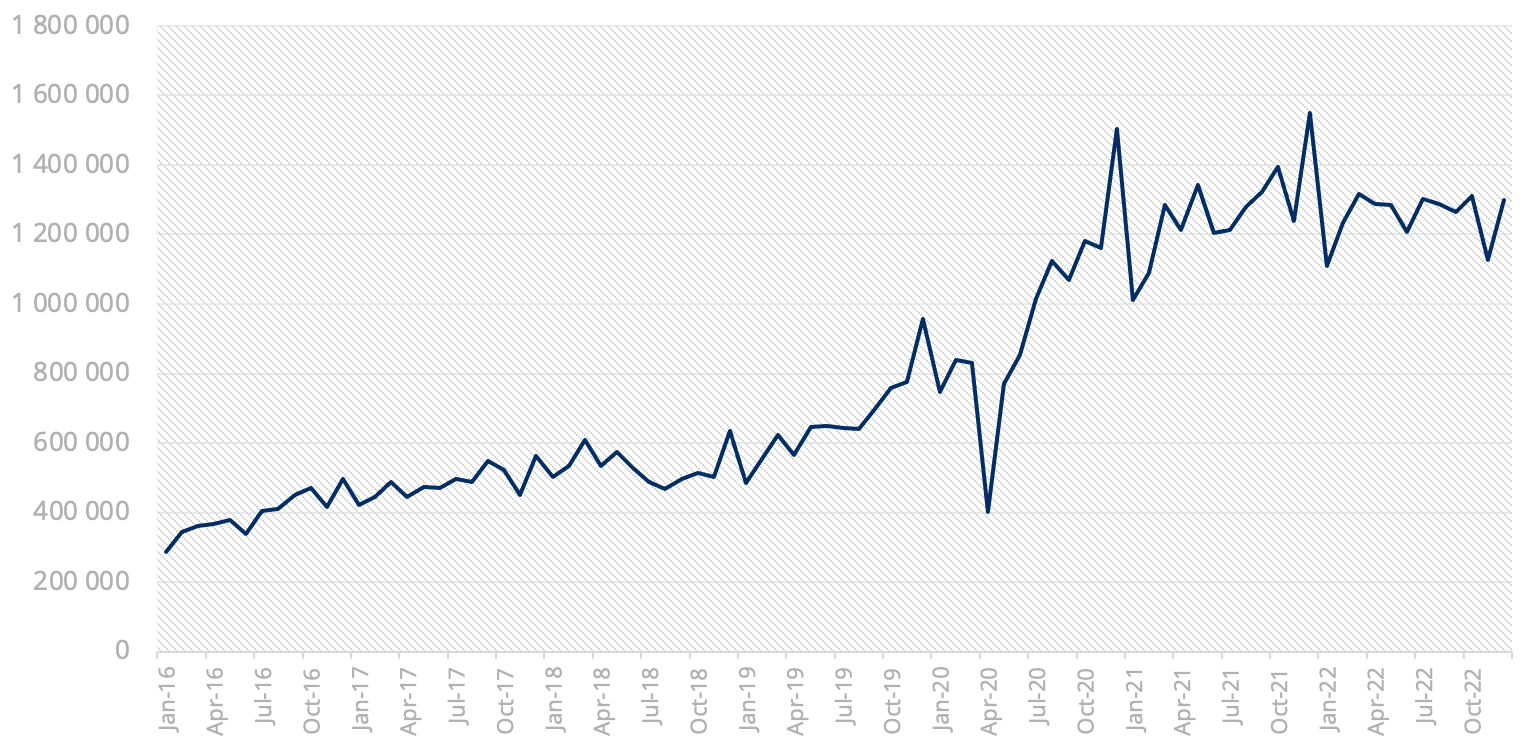

The number of formal remittance transactions (volume) outbound from South Africa since January 2016 has steadily risen by 3% month-on-month.

Total volume of formal remittances, South Africa outbound to the rest of SADC, 2016-2022

Source: South African Reserve Bank

Lindani Banda* is a 46-year-old man who financially supports his wife and five children. Faced with limited economic opportunities in his home country of Malawi, fourteen years ago he made the difficult decision to live apart from his family and relocate to South Africa in search of opportunities.

Arriving in Johannesburg with nothing but determination to improve his family circumstances, he relied on the generosity of migrants who had settled in South Africa before him for accommodation. His friends made space for him to share in their small house in the Alexandra Township in Johannesburg. Thanks to his social network, Lindani had a roof over his head when he started doing piecework and searching for permanent employment opportunities. He quickly found employment as a gardener twice a week for the Bernardo family in Houghton, a wealthy suburb about a ten-kilometre walk from where he was living.

Along with other piece jobs, the regular garden work provided Lindani with the stability to contribute financially to his shared living arrangements and send money to his family. However, he faced several challenges in his efforts to support his loved ones.

As a migrant worker in an informal room-sharing arrangement, Lindani lacked proof of residence, making it impossible for him to send money home via formal banking channels. At first, Lindani relied on his social network to send money home. He would ask acquaintances travelling to Malawi to take money to his relatives for a small fee and would do the same for others when he travelled home.

Sending money via friends and acquaintances was not always viable, and sometimes he needed to send money home urgently. In these instances, he would visit the Pan Africa Mall Taxi Rank where an informal taxi courier system operated. The courier allowed him to send money and packages to his family in Malawi. Although this method had its risks, like the inability to track or guarantee delivery, Lindani generally found it to be reliable. However, he often felt anxious while waiting for confirmation from his family that the parcels and cash arrived safely. Lindani also worried about his wife's safety when handling and carrying cash from the arranged pick-up points, but he had limited alternatives available to him.

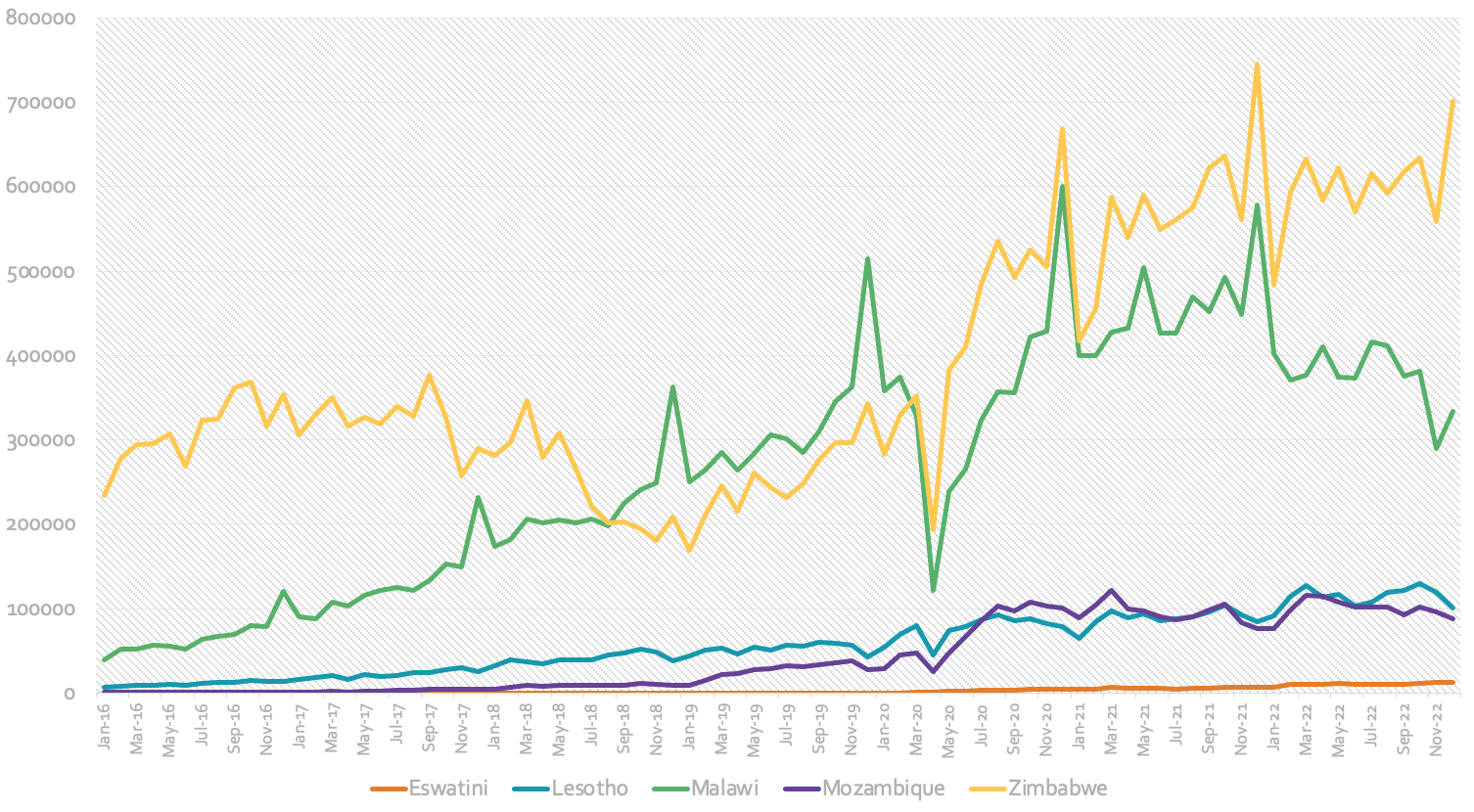

Remittances are lifelines to households and economies. In 2016, Zimbabwe received around 79% of formal outbound remittances, while Malawi accounted for nearly 17%. In 2022, Zimbabwe's share was 48% and Malawi's increased to 20%.

Total volume of formal remittances, South Africa outbound to Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, 2016-2022

Source: South African Reserve Bank

Lindani’s employment with the Bernardos became more regular. He started working for them four days a week as a handyman, gardener and helper in a small business they ran from their home. He also began working on his fifth day for their newly married daughter, Lisa, at her property in a nearby suburb.

Lisa found the inconvenience of paying him in cash frustrating, and opened a bank account for him in her name. Lindani used it as a post box to access cash. The transaction fees for sending money across the border through this account remained high, amounting to about 20%. As a result, Lindani and his, albeit improper, access to a digital store of value did not change his behaviour significantly.

After a few years, the Bernardos sold their large property and no longer needed Lindani on regular a basis. The Bernardo family’s social network, however, kept him employed five days a week. He worked for Lisa, some of her friends and Mr and Mrs Bernardo only one day of the five. Lindani’s handyman skills made him the go-to for minor renovations, which led to additional workdays and the occasional need to organise and manage additional workers for larger tasks. This provided an additional source of income.

Lindani’s new jobs meant travelling further, resulting in less frequent use of his walking route that passed by the Pan Africa Taxi Rank. Sending money using the taxi courier service became less convenient. However, a pieceworker who helped him with a house painting job told him about Mukuru, a remittance service that would allow him to deposit cash at a branch or with an agent in Johannesburg, and that his wife could collect the money from an agent in Malawi. Lindani switched to using Mukuru as it provided him with the peace of mind that his wife would get the cash safely, compared to the taxi courier service.

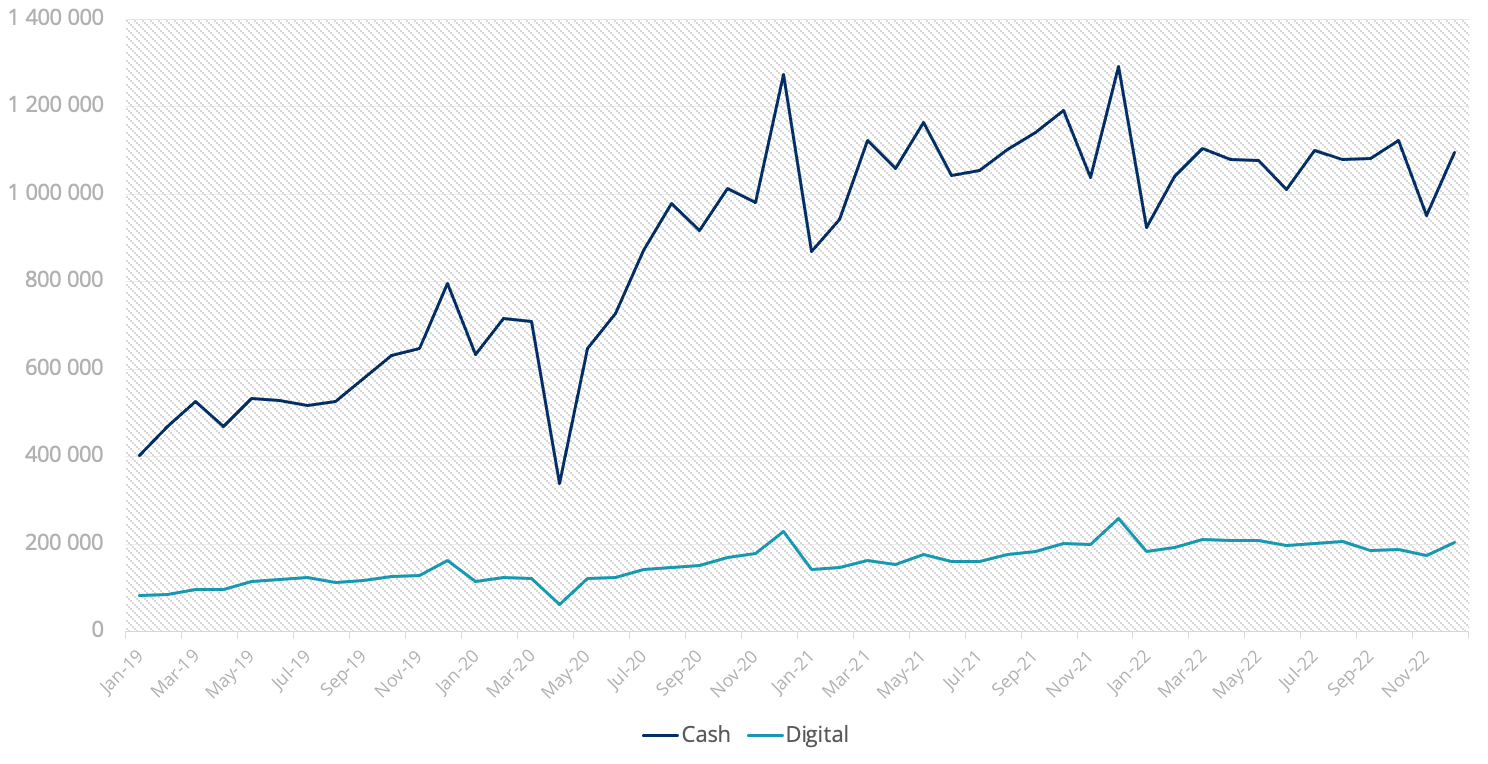

Fully digital transactions accounted for 16% of the total formal volumes sent in 2022, in 2021 they accounted for 17%. Non-banks have untapped potential to drive digitalisation at the first and last mile, which could be a catalyst for a decrease in remittance prices.

Total volume of formal remittances, South Africa outbound to the rest of SADC by cash or digitally, 2019-2022

Source: South African Reserve Bank

Like many, Lindani’s stable and regular income was threatened in 2020 when Covid-19 lockdowns were imposed, and he was unable to work due to the restrictions. He was fortunate that some of his employers continued to pay his wages during the lockdown. Border closures and restrictions on movement, however, meant that Lindani could not use his social network for cash transfers or reach a Mukuru branch to send money to his wife. A friend then showed him how transfer money digitally to his wife using his debit card details through Mukuru. This was a welcome solution for Lindani during the pandemic. However, once travel restrictions were lifted, he reverted to taking cash to the Mukuru office. Lindani generally uses his bank account as a post box for cash and this habit often means he does not have a digital balance to draw from.

Every migrant's story is unique, but there is a common thread in the challenges they face as remitters. While there are more digital options available to remitters today than there were ten years ago, cash still accounts for over 80% of formal remittances and a significant portion of funds sent are still going to fees.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 10.c commits to reducing the transaction costs of migrant remittances to less than 3% by 2030 and no corridor should have costs greater than 5%. This is premised on the fact that reducing the cost of remittance transfers can substantially increase disposable income for remittance-receiving families. Further, by reducing average costs to 3% globally, remittance families would save an additional USD20 billion annually.

For more than a decade FinMark Trust has been advocating for the reduction in the cost of digital remittances. Mystery shopping conducted in 2021 found average weighted prices in SADC to be 9.6%, down from 12.2% in 2019. The next step to reducing the price of remittances is the digitalisation of the first and last mile which forms a core focus of FinMark Trust’s programmes. Greater digitalisation, that reduces remittance pricing, will lead to better financial outcomes for those dependent on them.

Read the 2021 Remittances Market Assessment Report at https://finmark.org.za/Publications/Remittances_Market_Assessment_2021.pdf

*Names have been changed